A smartphone belonging to Drew Grande, 40, of Cranston, R.I., shows notes he made for contact tracing Wednesday, April 15, 2020. Grande began keeping a log on his phone at the beginning of April.

Steven Senne / AP Photo

A smartphone belonging to Drew Grande, 40, of Cranston, R.I., shows notes he made for contact tracing Wednesday, April 15, 2020. Grande began keeping a log on his phone at the beginning of April.

Steven Senne / AP Photo

Steven Senne / AP Photo

A smartphone belonging to Drew Grande, 40, of Cranston, R.I., shows notes he made for contact tracing Wednesday, April 15, 2020. Grande began keeping a log on his phone at the beginning of April.

(Pittsburgh) — One of the biggest challenges for contact tracing apps aimed at fighting COVID-19 is a lack of participation – and distrust in Western Pennsylvania appears to run particularly high, thanks in no small part to partisan feelings. But a team at Carnegie Mellon University thinks it can inspire greater buy-in with a new approach that helps users to prevent infection in the first place.

Standard contact tracing apps tell users if they’ve recently come into contact with other users who report being infected with COVID-19. Those who might have been exposed can then decide whether to quarantine in an effort to avoid spreading the disease.

That kind of technology becomes more effective as more and more people share their COVID status. Research suggests the tool works best when at least 60 percent of people participate.

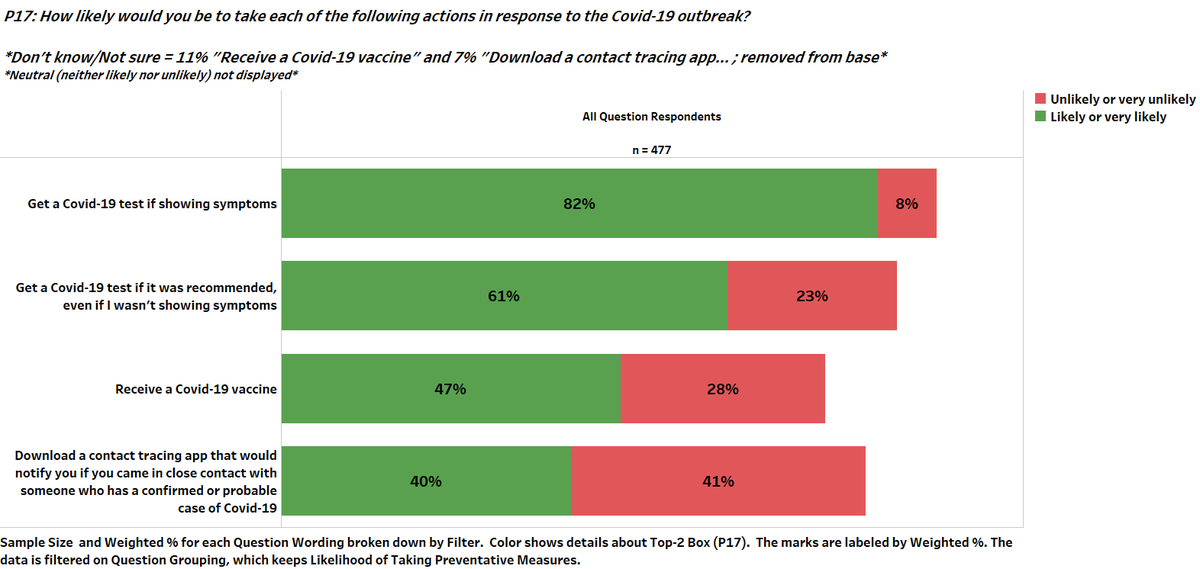

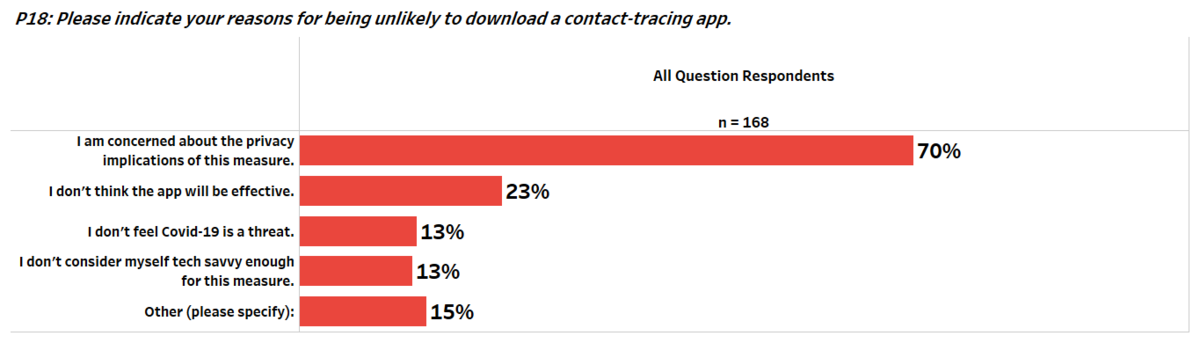

But in southwestern Pennsylvania, just 4 in 10 residents are likely to download contact tracing apps like one the state launched in September, according to the 90.5 WESA/Campos COVID Insights Study conducted between September 25 and October 9.

Tracing apps keep users anonymous and do not store location or personal information. But among the 41 percent of WESA/Campos survey respondents who said they were unlikely to download the technology, 70 percent reported concerns about its privacy implications. The survey also found that political party affiliation was a major point of division among respondents, with 56 percent of Democrats saying they are likely to use tracing apps, compared to only 22 percent of Republicans and 34 percent of Independents.

A 40-percent participation rate would be “obviously better than nothing,” Carnegie Mellon University computer science professor Jason Hong said. “But obviously higher is much better.”

90.5 WESA/Campos COVID Insights Study

A willingness to use the apps does seem higher in other parts of the country: National surveys show that about half of people are open to using the technology, despite privacy concerns. But so far in Pennsyvania, just 495,000 people, or about 4 percent of the state’s population, have downloaded the state’s tracing app, COVID Alert PA, which is available to people 17 and over, the Pennsylvania Department of Health said Tuesday.

Considering that reality, Hong said, “If we could get all 40 percent of people [from the WESA/Campos survey] to actually [download contact tracing apps] who said that they’d be interested in doing it, then it actually would have a positive effect in terms of blunting the spread of COVID, because the whole point of contact tracing is to cut off the chains of how it spreads. And so the faster you can find people and get them to quarantine, then the better it will be for everybody.”

90.5 WESA/Campos COVID Insights Study

It could be difficult to recruit more users in an environment where just 16 percent of people in Pennsylvania are willing to tell COVID-19 case investigators whether they recently visited a business or large gathering of people. But developers at Carnegie Mellon think they could entice greater participation with a fundamentally new approach.

Earlier this year, the CMU team rolled out a contact-tracing app that used an approach similar to apps like COVID Alert PA. But the latest version of NOVID tries to help people avoid exposure to the coronavirus altogether.

“There’s a difference between being reactive and being proactive,” said the app’s primary developer, Carnegie Mellon math professor Po-Shen Loh. “The standard paradigm only tells you after you’ve already been exposed, at which point the main purpose of the app is no longer [to give you] any way to do something about it. It’s mainly to help protect everybody else, which by the way, we should still do. But when you think about the incentive structure, our app actually aligns [with] natural incentives [for self-preservation].”

The newer version of NOVID, unveiled this summer, anonymously tracks COVID-19 and reports infections among those in users’ social circles and the people they interact with.

John Minchillo / AP Photo

In this April 20, 2020 photo, Catherine Hopkins, Director of Community Outreach and School Health at St. Joseph’s Hospital, right, performs a test on a patient in a COVID-19 triage tent at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Yonkers, N.Y. New York’s plan for taming the coronavirus hinges on taking a time-tested practice to an extraordinary level: hiring an “army” of people to try to trace everyone who might be infected. It’s part of a common approach to controlling infectious diseases — testing, tracing contacts and isolating those infected. But the scope is staggering even for a public health system that used the technique to combat AIDS and tuberculosis.

The app’s new design uses a chart to display the number of infections by varying degrees of proximity to the user. For example, those who come into direct contact with the user belong to the user’s first degree of separation. People who interact with those contacts comprise the user’s second degree of separation, and so on.

Loh said the developers have found that people are more willing to use such pre-exposure notification.

“Even if you are a really selfish person and you don’t care about anyone else,” he said, “it is to your great benefit to find out [your risk of infection] before COVID gets all the way to your contacts, as it’s coming into your contacts’ contacts. ”

Loh likened NOVID to a radar system “where we show everyone how far away COVID is striking from them.” Users can then decide whether to take measures such as wearing masks, avoiding gatherings, or sheltering in place.

Loh noted that economists have inquired about how that shift in mentality, where people no longer feel compelled to completely eliminate or ignore the risk of infection, could help to reopen the economy.

“If you were trying to drive at night and there were no headlights, then it would be so dangerous,” Loh said. “You’d have to tell everyone, ‘Please drive at two miles per hour because you can’t see anything. [But] once there are headlights, you can go at 65.’”

With about 90,000 users so far, the app has been deployed at Carnegie Mellon, Georgia Tech, Grand Valley State University in Michigan, and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. Local, state, and national governments across the globe have also inquired about the technology, according to Loh.

But he encouraged people to use standard contact tracing apps, too, to help combat COVID-19 on multiple fronts.

Sometimes, your mornings are just too busy to catch the news beyond a headline or two. Don’t worry. The Morning Agenda has got your back. Each weekday morning, host Tim Lambert will keep you informed, amused, enlightened and up-to-date on what’s happening in central Pennsylvania and the rest of this great commonwealth.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.