(Left to right) Julia R. Masterman School rising seniors Aden Gonzales, Nia Weeks, Tatiana Bennett, and Taryn Flaherty en route to turn in their historical marker application. December 2019.

Photo courtesy of Aden Gonzales

(Left to right) Julia R. Masterman School rising seniors Aden Gonzales, Nia Weeks, Tatiana Bennett, and Taryn Flaherty en route to turn in their historical marker application. December 2019.

Photo courtesy of Aden Gonzales

Photo courtesy of Aden Gonzales

(Left to right) Julia R. Masterman School rising seniors Aden Gonzales, Nia Weeks, Tatiana Bennett, and Taryn Flaherty en route to turn in their historical marker application. December 2019.

Though Alison Fortenberry was born in 2003, she wants you to remember 1967.

“[The 1967 student walkout] is not really something that’s really known in Philadelphia for this generation,” she said. “If we don’t have something tangible there, it’s just going to be another hidden part of Philadelphia’s history.”

Fortenberry is one of five Julia R. Masterman high school students who recently won approval from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission to honor the 1967 Black student walkout with a state marker. During the walkout, over 3,000 Philadelphia students protested racial injustice within the education system.

In the summer of 2019, Fortenberry was joined by fellow classmates Tatiana Bennett, Nia Weeks, Taryn Flaherty, and Aden Gonzales as they embarked on a three-month long research journey to learn more about the 1967 demonstration. Their ultimate goal was to prove the statewide and national significance of the event, which the historical commission requires of applicants seeking a state marker. Their project culminated in a 104-page document, which includes letters of endorsement from historians, oral history interviews with key participants, and an essay on the lasting impact the event had in the quest for racial justice.

Fortenberry spoke to Karen Asper Jordan, 71, who was only a year out of high school when she took part in the 1967 walkout.

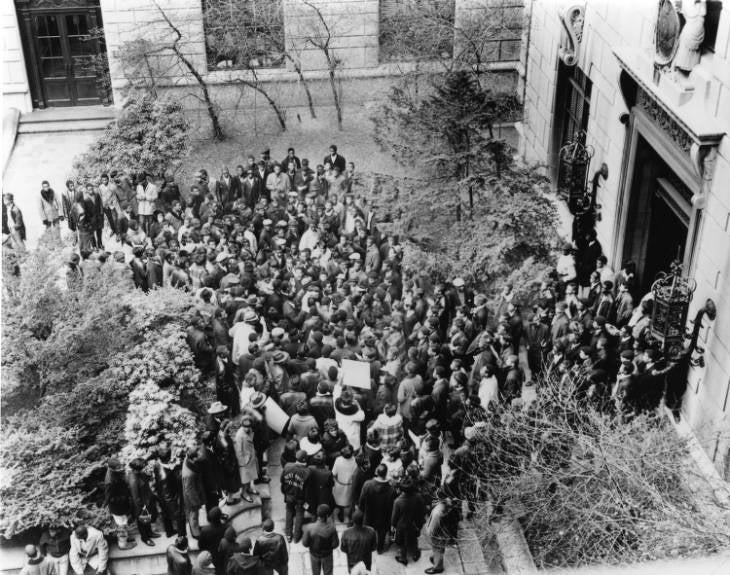

On November 17, 1967, African American high school students from across the city gathered in the courtyard of the Board of Education Building to protest racism and inequity within the school system. (Courtesy of the George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection at Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, Philadelphia, PA)

Hearing about the protests from elders who participated in them helped the students realize that the violence students faced that day was even worse than what the media had described.

“[Jordan] was telling us about how she was peacefully protesting and then … the police grabbed her shirt and dragged her down the street like half a block,” Fortenberry said. “Someone jumped on her to stop the police from dragging her. And then she and her friend both got beat and they were attacked with dogs.”

Matthew Countryman, a third-generation Germantown native, and professor of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan, served as a key source for the students. Countryman’s interests in 1960s Philadelphia began as a deeply personal connection: his parents met during the civil rights movement. And this interest developed into a book he wrote entitled, Upsouth, which traces the two generations of Black Philadelphians and their struggle for racial justice in the years between World War II and the 1970s.

Countryman helped them understand the level of segregation and disparity of opportunity and resources that existed in Philadelphia in the 1960s, especially in terms of housing, education and employment.

Between 1950 and 1970, Philadelphia experienced a period of rapid racial transformation. The city’s Black population almost doubled, increasing from 18% to 34% in those 20 years. As a result, neighborhoods that had once been predominantly white were quickly becoming mixed or predominantly Black.

On November 17, 1967, African American high school students from across the city gathered in the courtyard of the Board of Education Building to protest racism and inequity within the school system. (Courtesy of the George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection at Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, Philadelphia, PA)

Despite the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case of 1954, which said that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional, Philadelphia’s school board facilitated the segregation of its student body by redrawing school boundary lines in ways that kept schools racially homogenous even as neighborhood demographics shifted.

Neighborhood boundary lines designated where children could attend school, so if you lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood, your school was also predominantly Black. Because the Black population of Philadelphia was increasing, the predominantly Black schools were more likely to be overcrowded, and the redrawing of boundary lines prevented those children from going to the neighboring, predominantly white schools that had much more capacity. ‘

In 1963, a local civil rights organization called 400 Ministers asked the School District of Philadelphia to improve the conditions of about 60 predominantly Black schools, which were overcrowded, and lacked an equal distribution of school materials and certified teachers. The district responded by creating the Educational Improvement Program, which was meant to bring these schools up to par.

“These improvements, such as ending part-time classes, assigning certified teachers, and reducing class sizes were generally standard conditions in predominantly white schools at the time,” according to Anne E. Phillips, author of “The History of the Struggle for School Desegregation in Philadelphia: 1955-1967.”

Black teachers also felt the weight of inequity. In part due to the strength of the predominantly white teacher’s union, it was hard for Black teachers to receive professional development opportunities and pursue teacher certifications.

“There was all kinds of bias against teachers and students,” Countryman said. “Black teachers had a hard time getting the best kind of jobs, the best opportunities.” This meant Black students received the less-experienced teachers, which had a significant impact on the quality of courses offered at predominantly Black schools.

“You are beginning to have organizers say we want control of our own schools,” Countryman said. “We want to control our own businesses. We want to control our own communities. And that’s the lead into the 1967 walkouts.”

Taryn Flaherty, daughter of City Councilmember Helen Gym and a rising senior at Masterman, said it’s important to remember the student walkout of ‘67 as a carefully orchestrated event, as well as other civil rights demonstrations that were happening at the time.

“The students organized across the city,” Flaherty said. “It was a youth-led protest and there were several protests that came before this one.”

The walkout was built over three months of planning. Dr. Walter Palmer, a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania and a charter school founder, was then a few years out of high school and was the lead organizer of the demonstration.

Over the course of several months, he set up training sessions across majority-Black schools in the city, helping students develop organizing skills. Community leaders within the city’s many housing projects were assigned to distribute leaflets on key issues that plagued Black schools. A network of local Black church leaders and newspaper editors at The Philadelphia Tribune were also involved.

On the day of the protest, thousands of Black students walked out of class and converged at the Board of Education building.

Inside, two dozen students met with then-Superintendent Mark Shedd and then-Board Chairman Richardson Dilworth. They negotiated a list of 25 demands including a culturally inclusive curriculum and more Black teachers.

“They were trained in terms of how to present their demands,” Palmer said. “We did mock trials. They were given questions. They were told what the responses might be and how to answer it.”

Outside, things turned for the worse.

“While [district leaders are] literally meeting in the building with the student leaders, the students protesting outside get attacked by the police,” Countryman said.

The day became notorious for the brutality unleashed on student protesters under then-Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo’s leadership. News accounts depicted a peaceful demonstration turned ugly by nightstick-wielding police in riot gear. Karen Asper Jordan, shortly after being beaten by police herself, said she overheard a conversation between then-State Rep. Earl Vann and Rizzo as she sat handcuffed inside a police car.

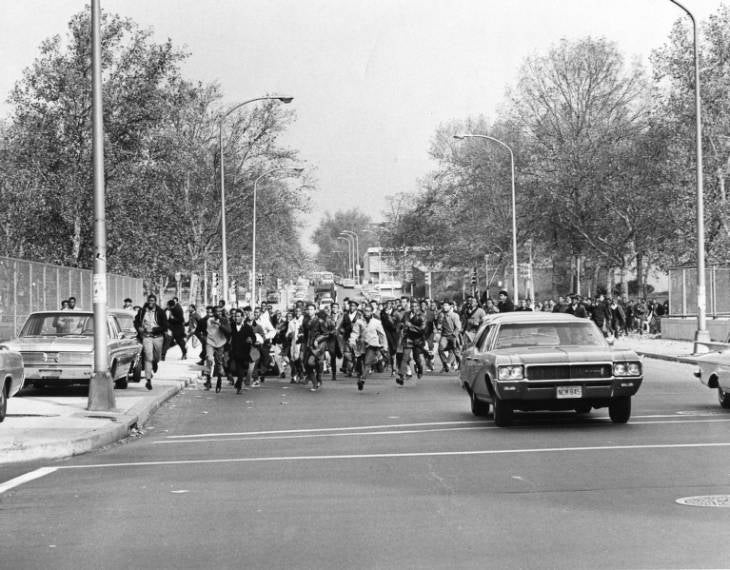

1967 Black student walkout demonstrators are attacked by Philadelphia police officers with nightsticks. (Courtesy of the George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection at Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, Philadelphia, PA)

“Earl Vann is begging Rizzo not to send the police on those children,” Jordan said. “I heard Earl Vann say, ‘They’re only children.’ Rizzo turned around and said, ‘Get their asses…’ and he really let loose on those children.”

Ultimately, 57 people were arrested and 22 were seriously injured.

The parallels between 1967 and recent protests, which led to the removal of the city’s Rizzo statue, are not lost among current Masterman students.

“We were all just thinking, how appropriate that it’s happening now,” Fortenberry said. “Finally Rizzo is going down. For so long he’s been a symbol of police brutality and oppression of student voices and minority voices. Now the plaque is going up and it’s a symbol of student voices — especially Black student voices.”

“I think [the walkout] shows how much change young people now can bring and how much of a strong voice we have in our city, our state, and our government,” Flaherty said. “Now there’s a new generation. These are young people who are leading the cause and we’re leading the change.”

Countryman said the demonstration set the precedent for all kinds of landmark education reform. Firstly, the demonstration foreshadowed the ethnic studies movement, as it called for the inclusion of African American curriculum within public school districts.

Immediately after the protest, a number of the high schools in the city — at the direction of the superintendent — created working groups between students and principals, which set the stage for a culture of cooperation between Black students and school administrators. In 2005, the School District of Philadelphia finally made African American history a required course for high school graduation, a first among America’s big cities.

Rising senior Tatiana Bennett said her student activism won’t stop after the historical marker is erected.

“[We’re] looking into how we can get microgrants for teachers who teach African American history,” Bennett said. “Or maybe even corresponding with other counties in the area, or other cities, about making a mandatory African American [history] class.”

For student Nia Weeks, learning more about this history nurtured a deep sense of pride within her as a Black Philadelphia native.

“It feels really special to be … a part of something that happened before I was even alive, before my parents were alive,” Weeks said.

Countryman said the kind of Black pride Weeks describes would have been central to the organizing work that happened in the ’50s and ’60s.

“If Black folks know their own history, they’ll have pride. They’ll have strength and solidarity,” said Countryman, “and this will be part of the motivation to demand justice.”

For the students, the approval of the plaque feels like a sliver of hope amid the recent acts of police brutality across the country. Now they’re trying to figure out where the historical marker will go.

1967 Black student walkout demonstrators rushing along 21st St. from the Parkway to the Board of Education. (Courtesy of the George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection at Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, Philadelphia, PA)

“We decided to put the marker outside the old Board of Education building, which is where the walkout took place,” student Aden Gonzales said. “We have to ask permission of the current owner of the building to put the marker there.”

Still, deep inequities persist in Pennsylvania public schools.

An analysis by the advocacy group POWER found that, even when controlling for poverty, state education spending is racially skewed — with predominantly white districts in the state getting more funding per student than those with more students of color.

During a group Zoom call with the students a week ago, Karen Asper Jordan gave the Masterman students advice for continuing to push for equality at all levels.

“We loved you before we knew you,” Jordan said. “We wanted to make the world a better place for those coming after us … When you go into battle, you’re never going into battle alone.”

“You may feel like you’re going in alone, but you got millions of people, millions of ancestors with you,” she added. “Take an ancestor, put a name in your pocket so you don’t feel that you’re alone.”

WHYY is the leading public media station serving the Philadelphia region, including Delaware, South Jersey and Pennsylvania. This story originally appeared on WHYY.org.

Get insights into WITF’s newsroom and an invitation to join in the pursuit of trustworthy journalism.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.